By Nina Rulie, 2025

This series of four articles—covering Maafa: Naming the Great Tragedy and Understanding Its Legacy, The Blues Aesthetic and Contemporary Resistance, African-American Dance Aesthetic, and Appreciate Without Appropriating: Dancing with Respect—offers an overview of African-American art forms, their history, and their contemporary significance.

Fil Rouge: Throughout this series, one central thread runs through all topics: art is inherently political. Music and dance have long been tools of resilience, resistance, and community building. The articles emphasize the importance of supporting one another, recognizing power dynamics, and creating inclusive spaces where culture is respected and shared responsibly.

Acknowledgments: I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Sabrina Ayorinde, educator and blues dancer based in Düsseldorf, whose collaboration and joint research with me for a cultural talk laid much of the groundwork for this series. Special thanks to Marie Ndiaye, Lindy Hop and African-American jazz dance choreographer, performer, educator, and researcher on ethnochoreography, and founder of Collective Voices For Change, who provided insight, encouragement, and valuable advice on cultural talks. I am also deeply thankful to Eda Özdek, with whom I share nurturing and supportive discussions. As an organizer, community builder, musician, and safe space coordinator, she plays a vital role in the blues and Lindy Hop community in Brussels. I am especially grateful for her invitation to write these articles and to publish them on the website. Finally, I thank all the Black, queer, and female dancers I have encountered, danced with, and spoken with, whose experiences and perspectives motivated me to write these articles.

Disclaimer: This series is based on a wide range of sources, including scholarly books, documentaries, interviews, and curated online materials. Readers are encouraged to consult these original sources for a deeper understanding and further exploration. Every claim, example, and historical context discussed here is drawn from the referenced works, which provide extensive insights into the rich tapestry of African-American cultural history.

CHAPTER 1 MAAFA

The Old Plantation (anonymous folk painting), 1780.

Maafa: Naming the Great Tragedy and Understanding Its Legacy

When we talk about the history of the transatlantic slave trade, words matter. The commonly used term “slave trade” emphasizes the economic aspect, as if it were merely a form of commerce. But for the descendants of those who suffered, this description is misleading.

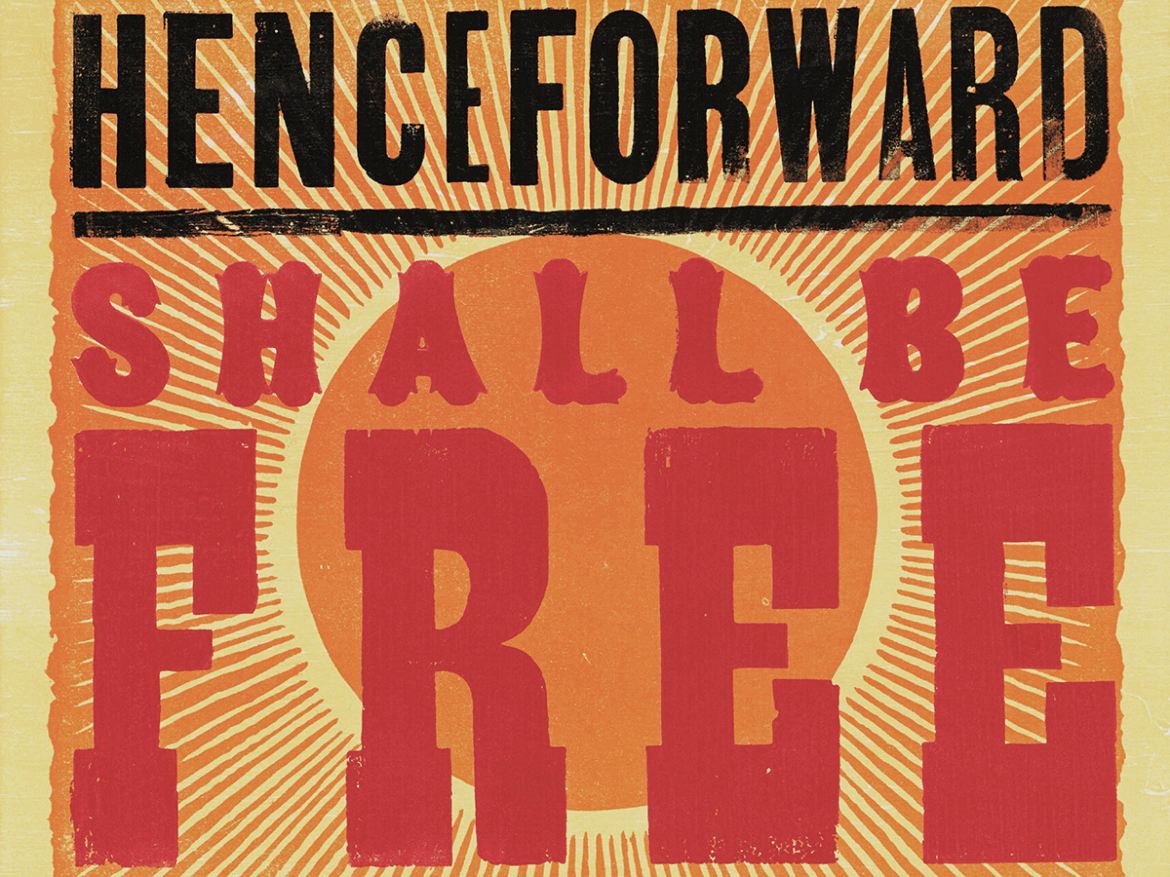

Since the late 1980s, another word has been used/ theorised: Maafa. In Kiswahili, a language spoken across East Africa, maafa means great catastrophe, disaster, or terrible tragedy. The term refers to the 350–400 years of enslavement and mass murder of millions of Africans (estimated at around 40 million) carried out by European and North American powers from the 16th to the 19th centuries.

This was not the first time in history that human beings had been enslaved — the ancient Greeks and Romans did so as well. But the new and horrifying aspect of the Maafa was its global scale, its systematization, and its institutionalization. As author and activist Tupoka Ogette points out, it was a form of exploitation of human beings carried out with an “extent of cruelty never seen before” (Ogette, 2020).

Enslaved Africans were stripped of all autonomy and subjected to unimaginable violence: whippings, mutilations, burnings, bondage, sexual exploitation, and complete denial of rights. The system was designed to dehumanize them and reduce their existence to forced labor and survival.

The Living Legacy: The Black Experience

Gail Anderson, ca. 2013. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Gail Anderson, © United States Postal Service

The Maafa did not end with abolition. Its effects are still visible today. The concept of the Black Experience captures what many African Americans face in the present — an everyday life shaped by the historical weight of slavery and systemic racism.

This experience manifests not only in overt racism — insults, discrimination, police violence — but also in more subtle, everyday interactions: microaggressions. These include questions like “Where are you really from?”, comments about appearance such as “You look so exotic”, or unconscious behaviors that reinforce negative stereotypes.

American writer and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates has powerfully described this reality. In his interviews and writings, he explains what it means to live with the constant awareness of vulnerability in a society shaped by racism. His testimony (see this video) provides a valuable insight into what is meant by the Black Experience.

Culture, Music, and Dance: Reclaiming Humanity

In the face of dehumanization, enslaved Africans turned to music, dance, and community rituals as lifelines of survival. These practices were not luxuries — they were necessities.

As Thomas DeFrantz notes in Stepping on the Blues (1996), music and dance became “a spiritual antidote to oppression; a way to lighten work, teach social values, and strengthen community institutions.” On both sides of the Atlantic, rhythm, song, and movement offered enslaved people a way to hold on to their dignity, express their inner feelings, and reconnect with their sense of humanity.

Dancing together, singing spirituals, or engaging in call-and-response rituals allowed communities to rebuild bonds shattered by forced displacement. Music and movement were deeply embodied acts of resistance ways to say: we are also human, intelligent and sophisticated.

In this sense, culture was more than expression: it was survival, healing, and community. It provided what the system of slavery tried to erase — a sense of belonging, identity, and resilience.

Listening, Learning, Recognizing

As Europeans, we cannot fully understand what it means to live the Black Experience in America and we should not pretend to. But what we can do is listen, learn, and cultivate empathy. Recognizing the Maafa and its ongoing legacy means refusing to see slavery as just a “chapter in history.” It means acknowledging how it shaped social relations, cultural perceptions, and systemic inequalities that are still with us today.

Today in the U.S. and around the world. Recognizing patterns of systemic inequality, cultural erasure, and social marginalization globally allows us to extend empathy and cultural awareness beyond national boundaries. Engaging with diverse histories and struggles fosters solidarity, a commitment to justice, and the affirmation of dignity for all oppressed communities. By understanding the Maafa and its enduring impact, we can appreciate how cultural expression not only preserves heritage but also inspires activism and cross-cultural empathy today.

→ If you want to dig more the subject of cultural awareness, competency and humility

Check this Ted talk, Juliana Mosley, Ph.D.

In the next article, we will explore how, music and dance became forms of resistance, survival, and expressions of humanity.

Sources

- Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Interview excerpt: YouTube.

- DeFrantz, Thomas F. Stepping on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. University of Illinois Press, 1996.

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Transatlantic Slave Trade.

- So You Want to Talk about Race by Ijeoma Oluo

- Angela Davis, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle

CHAPTER 2 BLUES AESTHETICS

“This is Harlem by Jacob Lawrence”, 1943, via Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC

The Blues Aesthetic: Heritage, Survival, and Contemporary Resilience

Music and Movement as Lifelines

As we explored in the previous article, Maafa (Kiswahili: “great disaster” or “tragedy”) refers to the centuries of enslavement and its lasting impact. In the face of unimaginable suffering, music and dance were far more than entertainment—they were lifelines. Through song, rhythm, and movement, African Americans nurtured their humanity, rebuilt community bonds, and found paths to healing even in the harshest conditions. These cultural practices were survival tools, acts of resistance, and affirmations of identity.

Blues Women and Everyday Freedom

Angela Y. Davis, in Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, book cover.

Angela Y. Davis, in Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, highlights how pioneering women like Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday transformed the blues into bold declarations of freedom. Their music voiced desire, independence, and resistance, articulating both personal and collective struggles.

- Ma Rainey, “Prove It On Me Blues” (1928): Celebrates identity and defiance with fearless honesty.

- Bessie Smith, “Young Woman’s Blues” (1926): Affirms autonomy and selfhood.

- Bessie Smith, “Backwater Blues” (1927): Chronicles resilience in the face of adversity.

- Billie Holiday, “Strange Fruit” (1939): Confronts the horrors of lynching with stark, unflinching truth.

Through their voices, the blues became more than music—it was a tool to articulate pain, claim agency, and assert everyday freedom. These women exemplified how cultural expression can be a form of empowerment and defiance.

The Blues Aesthetic

The blues is not just a genre; it is a philosophy of resilience. Houston A. Baker Jr., in Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature (1984), describes the blues aesthetic as a cultural logic that transforms struggle into meaning. The blues captures the lived experience of Black people in America, carrying both the memory of oppression and the creative strategies for survival, joy, and transformation that emerge from it.

Baker emphasizes “mastery and deformation”—taking dominant Western forms and reshaping them into expressions uniquely reflective of Black life. Pain, hardship, and everyday struggles are transformed into art that is resilient, witty, and deeply rooted in community.

Jazz legend Wynton Marsalis echoes this philosophy:

“It is our spiritual view, which is optimism in the face of adversity. … How do you use what you have to be resilient and to deepen your humanity through the tragedy and the struggle? … The feeling that we call soul comes out of the Blues aesthetic and it’s an essential ingredient to our music.”

The blues aesthetic is a lens through which literature, dance, and music resonate with lived experience—simultaneously documenting history and imagining new possibilities. From sacred ring shouts to juke joints, jazz improvisations, hip-hop cyphers, and contemporary multimedia performances, it is a continuous thread of Black creativity, endurance, and spiritual resilience.

Evolution of Sound and Movement

Getty images

The blues aesthetic has evolved across genres, movements, and communities, shaping the rhythms of resistance and joy.

- Blues → Jazz & Social Dance: Improvisation fuels the Lindy Hop, turning ballrooms into spaces of collective celebration and subtle defiance.

- Soul, Funk, Gospel: Songs became sermons of justice and resilience, echoing during the Civil Rights and Black Power movements.

- Hip-Hop & House: Dance circles reemerged as liberation spaces for Black, Latinx, and queer communities.

- Global Flow: From Amapiano in South Africa to samba in Brazil and French rap, the blues aesthetic continues to travel, adapt, and thrive.

Contemporary Resilience in Song & Performance

Today’s Black American artists carry forward the lineage of endurance, improvisation, and social critique that defines the blues aesthetic:

- Little Simz – “Pressure” (2021): Confronts systemic oppression with rhythm and artistry.

- Rapsody – “Nina” (2019): Honors Nina Simone and celebrates Black women’s resilience.

- Vince Staples – “Hands Up” (2014): Captures the Ferguson protests through music.

- Common & John Legend – “Glory” (2014): Bridges civil-rights history with present struggles.

- Childish Gambino – “This Is America” (2018): Potent visual and musical critique of contemporary violence.

- H.E.R. – “I Can’t Breathe” (2020): Mourns and resists through song.

- Lil Baby – “The Bigger Picture” (2020): Channel collective pain into urgent reflection and empowerment.

- Kendrick Lamar – “Alright” (2015): A modern anthem of hope and persistence.

- Damon Locks – List of Demands (2025) & Moor Mother – The Great Bailout (2023): Interweave history, incarceration narratives, and colonial critique.

- Doechii – “Alligator Bites Never Heal” (2025): Challenges genre conventions, embraces queer identity, echoing the fearless spirit of blueswomen.

Across genres and generations, black artists demonstrate how music and performance continue to serve as vessels for resilience, resistance, and communal expression.

→ Explore rhythm, resistance, and spirit of African American creativity

Check this playlist.

Sources & Further Reading

- Davis, Angela Y. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism. Vintage, 1998.

- Baker, Houston A. Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature. Univ. of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Malone, Jacqui. Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1996.

- Wynton Marsalis, Serie Wynton at Harvard from Jazz at Lincoln Center (accessible on youtube)

- Durden, Moncell. Everything Remains Raw [Documentary].

- Powell, Richard, curator. The Blues Aesthetic: Black Culture and Modernism. Washington Project for the Arts, 1990.

CHAPTER 3 The African-American Dance Aesthetic: Roots, Expression, and Community

Jitterbugging in a juke joint on Saturday evening outside Clarksdale, November 1939 (Marion Post Wolcott, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. [LC-USF34- 052594-D])

The African-American Dance Aesthetic: Roots, Expression, and Community

Building on the heritage of the Maafa and the blues aesthetic, African-American dance represents a living archive of cultural resilience. It embodies survival, expression, and identity through movement, connecting historical struggles with contemporary creativity. Dance carries memory, emotion, and communal knowledge, offering a lens through which to understand African-American history and values.

Foundations and Key Principles

While music and dance as survival strategies were discussed in the context of the blues aesthetic, dance itself emphasizes core principles that shape the African-American aesthetic:

- Grounded movement: Dancers maintain a deep connection to the earth, with energy flowing from the feet through the spine. This grounding provides stability while allowing fluid and dynamic movement.

- Polyrhythmic expression: Multiple rhythms are layered simultaneously, both in body movement and coordination with music, creating complex and syncopated patterns.

- Isolations and articulations: Unique control of body segments—hips, shoulders, torso, and spine—allows expressive storytelling and nuanced emotional expression.

- Call-and-response: Movement interacts with other dancers, musicians, and audience, creating a dialogue that mirrors African communal dance practices.

- Community focus: Beyond personal expression, dance fosters cohesion and collective experience, emphasizing shared energy, mutual respect, and support within a social context.

- Improvisational foundation: While rooted in specific techniques, dancers are encouraged to innovate and personalize movements, reflecting individual identity within the collective aesthetic.

These principles originate in African traditions and inform the choices of African-American dancers today, providing both a link to historical practices and a platform for contemporary creativity.

Soul Train: Televised musical program featured dancers showcasing the freschest moves.. Photo circa 1970. – Getty Images

Social and Community Dance

African-American social dances—such as the ring shout, vernacular jazz dances, and Lindy Hop—serve purposes that extend beyond entertainment:

- Spiritual and emotional resilience: Movements provided a ritualized way to maintain faith, express hope, and endure oppression.

- Storytelling and communication: Dance was a medium to narrate personal and collective experiences, encode social values, and transmit history.

- Community cohesion: Participation in social dances built trust, solidarity, and intergenerational connections. The community was both participant and witness, making dance a shared and interactive practice.

These functions continue in contemporary social dance settings, reinforcing cultural continuity and mutual support.

Improvisation and Identity

Improvisation remains central to African-American dances, shaping personal expression and community interaction:

- Spontaneity within structure: Core movements offer a framework, but dancers can invent variations in real-time.

- Competitive camaraderie: Jam circles and informal contests encourage excellence while fostering encouragement, respect, and mentorship.

- Balance of individuality and collectivity: Each dancer projects their unique identity while contributing to a shared aesthetic, reinforcing interdependence within community.

- Emotional articulation: Improvisation allows dancers to externalize inner feelings, engage with music in a conversational way, and connect with audiences emotionally.

The Aesthetic of Cool

Distinct from the blues aesthetic discussion, the dance-specific idea of coolness embodies both technical mastery and cultural values:

- Effortless mastery: Technical skill is integrated seamlessly with personal style.

- Controlled energy: Movements are expressive yet intentional, reflecting discipline and focus.

- Composure and dignity: Even in energetic or acrobatic sequences, dancers convey poise and self-possession.

- Cultural expression: Coolness serves as a metaphor for resilience, calm confidence, and the assertion of identity under social pressure.

The Nasty Boys at the 1993 Folklife Festival. Photo by Jeff Tinsley, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

The African-American dances aesthetic, while intertwined with the blues and musical traditions previously discussed, is a distinct field of embodied expression. It is a living archive of history, a platform for innovation, and a testament to the enduring power of community, resilience, and cultural identity.

→ If you want to know more about African American aesthetic through art:

I recommend the work of Luana, What Makes That Black?: The African American Aesthetic in American Expressive Culture (2018).

Here is a recording of a lecture she provided at two schools in the San Francisco Bay Area:

Sources & Further Reading

- Luna, What Makes That Black?: The African American Aesthetic in American Expressive Culture, 2018.

- Malone, Jacqui. Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1996.

- Crosby, Jill Flanders & Moss, Michel. Jazz Dance: A History of Roots and Branches.

- N’diaye, M. M. (2023). Rhythmic Resilience: An exploration of the African American Lindy Hop Community in New York City, USA (Master’s thesis, NTNU).

- Durden, Moncell. Everything Remains Raw [Documentary].

- Frankie Manning Foundation, oral histories and interviews.

- Vogue and Waacking histories: Paris is Burning (documentary), archives from Ballroom culture.

- The history of African-American social dance – Camille A. Brown, Ted Ed (accessible on Youtube)

- Generations of African American Social Dance in D.C.: Hand Dancing, Hip-Hop, and Go-Go, September 20, 2016, LeeEllen Friedland, Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

CHAPTER 4 Appreciate Without Appropriating: Dancing with Respect

“Until We Get There,” 2018, Mehran Heard, mural located at the corner of Northeast Alberta Street and Martin Luther King Jr Boulevard in Portland.

Appreciate Without Appropriating: Dancing with Respect

As we discussed in the previous articles, African-American art forms are more than entertainment; they are living expressions of history, resilience, and community. These dances are deeply political, born from struggles against oppression and inequality. To dance them with integrity is to honor the social, cultural, and political contexts from which they emerged. By understanding this heritage, dancers from all backgrounds can engage with the art respectfully, appreciating its depth while celebrating its vibrancy.

Cultural Competence in our dance scenes

True cultural competence goes beyond learning steps; it is about understanding the story behind the movement. It invites dancers to:

- Embrace history: Recognize the origins of movements, dances, and music, along with the social, political, and cultural contexts that shaped them.

- Engage respectfully: Approach the community with humility, listen attentively, and learn from cultural bearers.

- Reflect on privilege: Acknowledge advantages—whether racial, social, or positional—and use them to foster inclusion and equity rather than division.

- Acknowledge inequalities: Recognize the historical and ongoing oppressions that inform these dance traditions and honor them through solidarity and support.

From Technique to Meaning

Mastering technique is only the beginning. African-American dances are rooted in community and lived experience:

- Express individuality through understanding: Let your improvisation and style reflect informed appreciation rather than mimicry.

- Honor the community: Many dances, thrive on interaction; they are as much about connection as about movement.

- Live the values: Coolness, resilience, joy, and improvisation are not just stylistic; they carry cultural and political significance.

The Sugar Shack, 1976 Ernie Barnes, Acrylic on canvas.

Power, Responsibility, and Inclusive Spaces

Every dancer occupies a unique position in the community, and with visibility comes responsibility. Relating power to cultural appreciation and awareness involves:

- Recognize your power: Some dancers may teach, perform, or organize, while others participate more quietly. Each position carries potential to influence.

- Act responsibly: From learning respectfully to advocating for inclusion, uplifting others, and standing against inequities, everyone can make meaningful contributions.

- Bridge power and appreciation: Cultural competence and awareness translate into creating safe, welcoming, and politically aware spaces.

- Invite collective participation: Acknowledge different power levels and encourage every dancer to contribute, ensuring that the community is inclusive, equitable, and supportive.

Contemporary Practices and Sensitivity

Modern dance spaces—festivals, social events, and online communities—offer opportunities to practice respect, solidarity, and cultural awareness:

- Give credit: Acknowledge the origins and lineage of the dances you perform.

- Learn from the community: Seek guidance from experienced dancers connected to the culture.

- Adapt mindfully: While evolution and fusion are natural, avoid erasing or misrepresenting the source culture.

- Promote equity and support: Create spaces where marginalized voices are centered and all participants feel safe, supported, and valued.

Blues Dancing Series #4 The Kind of Blues That Don’t Bring You Down. Oil on Wood, June 2019, Laura Gillen

Embracing the Spirit of the Dance

Appreciating without appropriating means embodying the deeper values and politics of the culture:

- Empathy and solidarity: Connect with the struggles and resilience encoded in the dance.

- Community connection: Honor the improvisational dialogue and interactive traditions.

- Purposeful responsibility: Use your presence and skills to promote understanding, respect, and cultural continuity.

Engaging with African-American dance respectfully enhances personal expression, strengthens communities, and preserves cultural heritage. By learning history, understanding values, acknowledging positional power, recognizing inequalities, and acting with humility and solidarity, dancers of all levels can celebrate the art authentically, creating a safe, inclusive, and politically conscious global dance culture.

→ Interested into how to Address the issues of racial inequalities and cultural appropriation into the dance scene?

Check the CVFC conferences replays

Sources & Further Reading

- Collective Voices For Change [Website].

- Grey Armstrong – A Blackness and Blues Blog – Obsidian Tea

- Durden, Moncell. Everything Remains Raw [Documentary]